The synthesis of 1a~1o was according to the previously reported method.[6a-6b]

4-(1-(Diphenylsilyl)vinyl)benzyl 2-((3-(trifluorometh- yl)phenyl)amino)nicotinate (1o): White solid, m.p. 91.6~94.7 ℃ [V(petroleum ether, PE)∶V(ethyl acetate, EA)=10∶1]. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 10.33 (s, 1H), 8.40 (dd, J=4.4, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (dd, J=8.0, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (s, 1H), 7.86 (d, J=8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.60~7.53 (m, 4H), 7.45~7.31 (m, 11H), 7.29~7.26 (m, 1H), 6.76 (dd, J=4.8, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 6.30 (d, J=1.2 Hz, 1H), 5.71 (d, J=2.4 Hz, 1H), 5.39 (s, 1H), 5.32 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 167.2, 155.8, 153.1, 145.4, 143.3, 140.34, 140.28, 135.7, 134.1, 132.8, 132.7, 131.1 (q, JC—F=32.1 Hz), 129.9, 129.2, 128.4, 128.1, 127.0, 124.1 (q, JC—F=272.7 Hz), 123.5, 119.0 (q, JC—F=3.9 Hz), 117.1 (q, JC—F=3.9 Hz), 114.1, 107.4, 66.8; 19F NMR (376.5 MHz, CDCl3) δ: -62.6; IR (neat) ν: 2129, 1691, 1611, 1586, 1529 cm-1; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C34H28F3N2O2Si (M+ H+) 581.1867, found 581.1865.

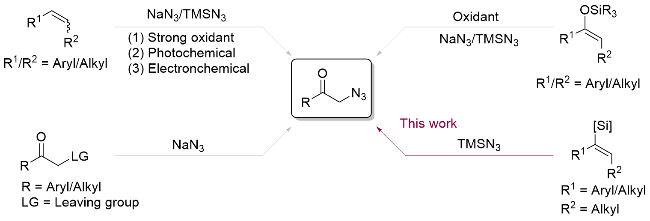

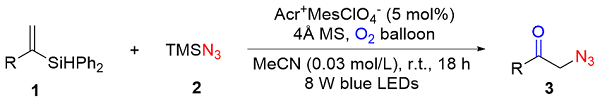

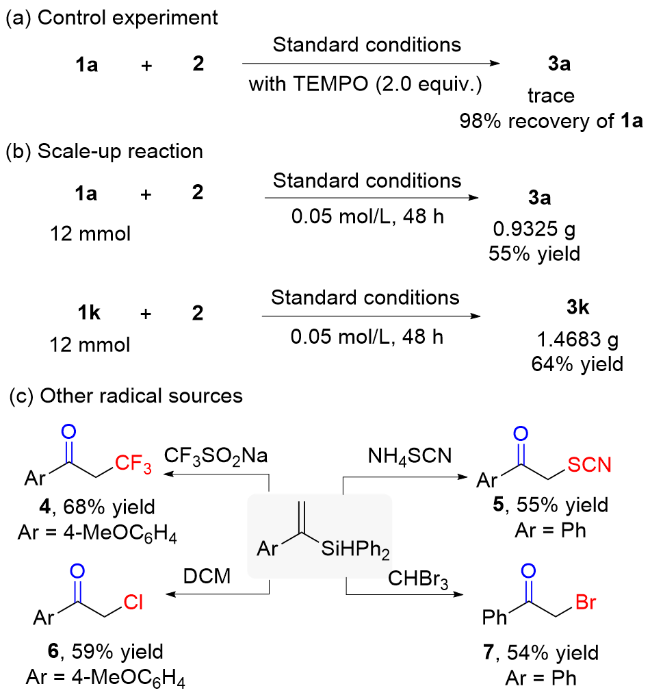

To a 25 mL overdried Schlenk flask with magnetic stirrer were added 1 (0.3 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), Acr+$\mathrm{MesClO}_{4}^{-}$ (6.2 mg, 0.015 mmol, 5 mol%), 4 Å MS (w=100% based on 1). Then, the tube was evacuated and backfilled with oxygen. Subsequently, 2 (80 μL, 2.0 equiv.) and dry MeCN (10 mL) were added by syringes. The reaction mixture was stirred under the irradiation of 8 W blue LEDs for 18 h. After that the reaction was quenched by petroleum ether, filtered through a short pad of silica and eluted with ethyl acetate. The combined filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure and purified by flash column chromatography to afford the corresponding products 3a~3o and 2ab.

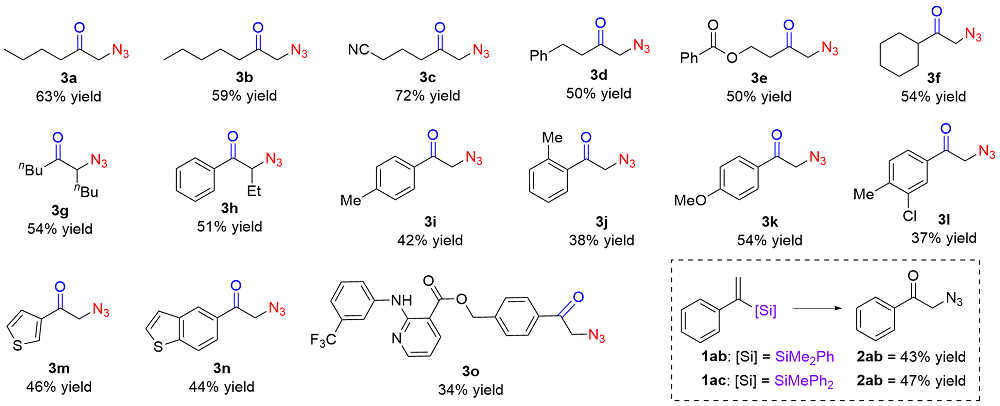

1-Azidohexan-2-one (3a): Colorless oil (26.7 mg, 63% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 3.94 (s, 2H), 2.45 (t, J=7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.65~1.56 (m, 2H), 1.39~1.28 (m, 2H), 0.92 (t, J=7.6 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 204.6, 57.4, 39.8, 25.5, 22.2, 13.7; IR (neat) ν: 2961, 2102, 1726, 1416, 1281 cm-1; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C6H11- N3NaO (M+Na)+ 164.0794, found 164.0794.

1-Azidoheptan-2-one (

3b):

[14] Colorless oil (27.5 mg, 59% yield).

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl

3)

δ: 3.93 (s, 2H), 2.44 (t,

J=7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.67~1.59 (m, 2H), 1.36~1.27 (m, 4H), 0.90 (t,

J=6.8 Hz, 3H);

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl

3)

δ: 204.6, 57.4, 40.0, 31.2, 23.1, 22.3, 13.8.

6-Azido-5-oxohexanenitrile (3c): Colorless oil (32.9 mg, 72% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 3.99 (s, J=6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.67 (t, J=6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.47 (t, J=6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.04~1.95 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 202.8, 118.9, 57.4, 37.7, 18.8, 16.4; IR (neat) ν: 2918, 2105, 1728, 1419, 1277 cm-1; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C6H8N4NaO (M+Na)+ 175.0590, found 175.0588.

1-Azido-4-phenylbutan-2-one (

3d):

[14] Colorless oil (28.4 mg, 50% yield).

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl

3)

δ: 7.32~7.26 (m, 2H), 7.24~7.15 (m, 3H), 3.86 (s, 2H), 2.95 (t,

J=7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.76 (t,

J=7.2 Hz, 2H);

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl

3)

δ: 203.6, 140.2, 128.6, 128.3, 126.4, 57.6, 41.6, 29.4.

4-Azido-3-oxobutyl benzoate (3e): Colorless oil (35.0 mg, 50% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.00 (d, J=7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.57 (t, J=7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (t, J=8.0 Hz, 2H), 4.63 (t, J=6.0 Hz, 2H), 4.03 (s, 2H), 2.94 (t, J=6.0 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 201.6, 166.3, 133.2, 129.64, 129.59, 128.4, 59.3, 57.8, 39.2; IR (neat) ν: 3002, 2105, 1719, 1602, 1454 cm-1; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C11H11N3NaO3 (M+Na)+ 256.0693, found 256.0694.

2-Azido-1-cyclohexylethan-1-one (

3f):

[15] Colorless oil (27.1 mg, 54% yield).

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl

3)

δ: 3.99 (s, 2H), 2.45~2.37 (m, 1H), 1.87~1.77 (m, 4H), 1.72~1.64 (m, 1H), 1.45~1.17 (m, 5H);

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl

3)

δ: 207.2, 55.8, 48.3, 28.2, 25.6, 25.4.

6-Azidodecan-5-one (3g): Colorless oil (32.0 mg, 54% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 3.78 (dd, J=8.4, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 2.54~2.48 (m, 2H), 1.82~1.74 (m, 1H), 1.71~1.63 (m, 1H), 1.62~1.55 (m, 3H), 1.43~1.29 (m, 5H), 0.95~0.90 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 207.8, 68.1, 39.3, 30.5, 27.9, 25.4, 22.3, 22.2, 13.8; IR (neat) ν: 2959, 2875, 2100, 1722, 1605, 1453 cm-1; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C10H19N3NaO (M+Na)+ 220.1420, found 220.1419.

2-Azido-1-phenylbutan-1-one (

3h):

[14] Colorless oil (28.3 mg, 51% yield).

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl

3)

δ: 7.94 (d,

J=6.8 Hz, 2H), 7.62 (t,

J=7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (t,

J=8.0 Hz, 2H), 4.54 (dd,

J=8.4, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 2.06~1.95 (m, 1H), 1.93~1.82 (m, 1H), 1.08 (t,

J=7.2 Hz, 3H);

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl

3)

δ: 196.7, 134.8, 133.9, 128.9, 128.5, 64.5, 24.8, 10.6.

2-Azido-1-(

p-tolyl)ethan-1-one (

3i):

[4] White solid (22.1 mg, 42% yield), m.p. 60.7~62.7 ℃ (CDCl

3) (lit.

[20] 60~61 ℃);

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl

3)

δ: 7.81 (d,

J=8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.30 (d,

J=8.0 Hz, 2H), 4.54 (s, 2H), 2.43 (s, 3H);

13C NMR (100 MHz)

δ: 192.8, 145.2, 131.9, 129.6, 128.0, 54.7, 21.7.

2-Azido-1-(

o-tolyl)ethan-1-one (

3j):

[4] Colorless oil (20.0 mg, 38% yield).

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl

3)

δ: 7.57 (d,

J=7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (t,

J=7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.33~7.27 (m, 2H), 4.45 (s, 2H), 2.56 (s, 3H);

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl

3)

δ: 196.3, 139.5, 134.3, 132.53, 132.49, 128.3, 125.9, 56.4, 21.5.

2-Azido-1-(4-methoxyphenyl)ethan-1-one (

3k):

[4] White solid (31.0 mg, 54% yield), m.p. 72.8~73.5 ℃ (CDCl

3) (lit.

[20] 69~70 ℃);

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl

3)

δ: 7.89 (d,

J=8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.96 (d,

J=8.8 Hz, 2H), 4.51 (s, 2H), 3.89 (s, 3H);

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl

3)

δ: 191.6, 164.2, 130.3, 127.3, 114.1, 55.5, 54.5.

2-Azido-1-(3-chloro-4-methylphenyl)ethan-1-one (3l): White solid (23.8 mg, 37% yield), m.p. 78.7~80.1 ℃ (DCM); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.88 (d, J=1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (dd, J=8.0,1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (d, J=8.0 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (s, 2H), 2.45 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 191.8, 143.0, 135.3, 133.5, 131.4, 128.6, 126.0, 54.8, 20.5; IR (neat) ν: 2112, 1685, 1602, 1446, 1220 cm-1; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C9H8ClN3NaO (M+Na)+ 232.0248, found 232.0249.

2-Azido-1-(thiophen-3-yl)ethan-1-one (

3m):

[16] Colorless oil (23.1 mg, 46% yield).

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl

3)

δ: 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.55 (d,

J=4.0 Hz, 1H), 7.41~7.37 (m, 1H), 4.44 (s, 2H);

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl

3)

δ: 187.6, 139.0, 132.7, 127.1, 126.5, 55.4.

2-Azido-1-(benzo[b]thiophen-5-yl)ethan-1-one (3n): Colorless oil (28.7 mg, 44% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.37 (d, J=1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.97 (d, J=8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (dd, J=8.4, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (d, J=5.6 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (d, J=5.6 Hz, 1H), 4.65 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 193.0, 145.2, 139.4, 130.8, 128.4, 124.5, 123.9, 123.0, 122.8, 54.9; IR (neat) ν: 2917, 2105, 1686, 1592, 1425 cm-1; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C10H7N3NaOS (M+Na)+ 240.0202, found 240.0204.

4-(2-Azidoacetyl)benzyl 2-((3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)- amino)nicotinate (3o): Colorless oil (46.4 mg, 34% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 10.27 (s, 1H), 8.43 (dd, J=4.4,1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.32 (dd, J=8.0, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.06 (s, 1H), 7.95 (d, J=8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.87 (d, J=8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (d, J=8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.43 (t, J=8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (d, J=7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.81 (dd, J=7.6, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 5.44 (s, 2H), 4.56 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 192.7, 167.0, 155.8, 153.5, 141.8, 140.2, 140.1, 134.2, 131.0 (q, JC—F=32.2 Hz), 129.7, 128.3, 128.2, 124.1 (q, JC—F=273.0 Hz), 123.6, 119.1 (q, JC—F=3.7 Hz), 117.1 (q, JC—F=3.7 Hz), 114.1, 106.8, 86.0, 54.8; 19F NMR (376.5 MHz, CDCl3) δ: -62.6; IR (neat) ν: 2104, 1692, 1584, 1529, 1445 cm-1; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C22H17F3N5O3 (M+H)+ 456.1278, found 456.1276.

2-Azido-1-phenylethan-1-one (

2ab):

[4] Colorless oil (20.8 mg, 43% yield).

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl

3)

δ: 7.91 (d,

J=7.60 Hz, 2H), 7.63 (t,

J=7.60 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (t,

J=7.60 Hz, 2H), 4.57 (s, 2H);

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl

3)

δ: 193.2, 134.4, 134.1, 129.0, 127.9, 54.9.