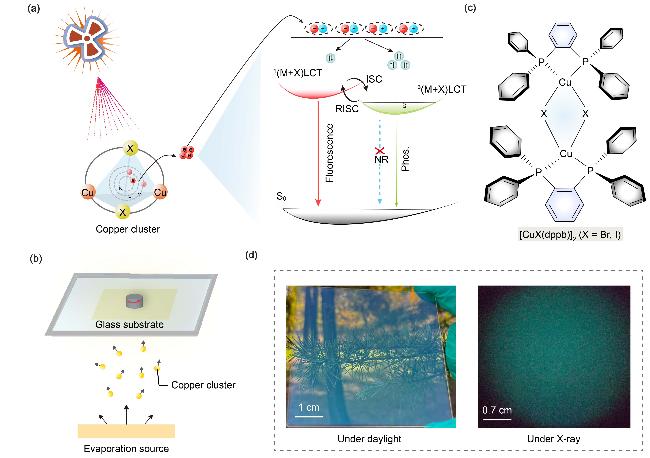

The excellent crystal luminescence and high atomic number of halogen atoms (Br, I) forebode the promising potential of

[CuX(dppb)]2 clusters as X-ray scintillators. Therefore, a systematic study of the scintillation performance of

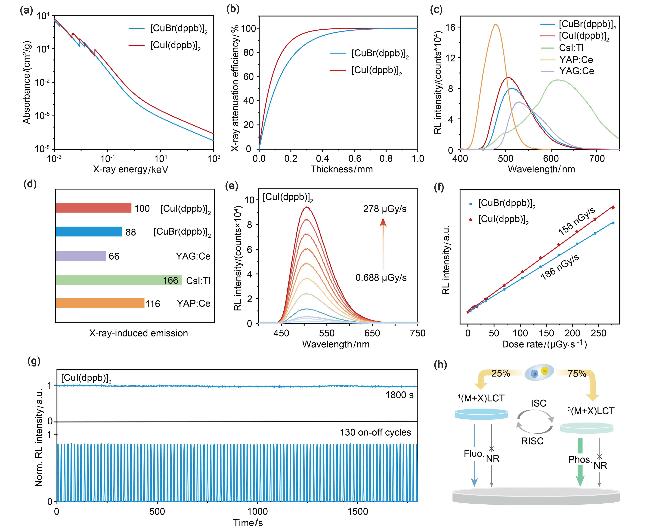

[CuX(dppb)]2 under X-ray excitation was conducted. Since the X-ray absorption coefficient (

α) is proportional to the fourth power of the atomic number,

[40] [CuI(dppb)]2 (

Zmax=53,

Kα=33.17 keV) containing iodine atoms exhibits the stronger X-ray absorption in comparison with

[CuBr(dppb)]2 (

Zmax=35,

Kα=13.47 keV) (

Figure 3a). Subsequently, the attenuation of

[CuX- (dppb)]2 as a function of thickness was calculated at an X-ray photon energy of 68 keV. It was found that a 0.4-mm-thick

[CuI(dppb)]2 can attenuate 99% of X-ray photon energy, while

[CuBr(dppb)]2 requires a thickness of 0.68 nm (

Figure 3b).

Figure 3c shows the RL spectra of 50 mg

[CuX(dppb)]2 crystals compared to commercial scintillators CsI:Tl, Ce:YAP, and Ce:YAG powders under the same X-ray dose rate irradiation.

[CuX(dppb)]2 crystals manifest the excellent X-ray scintillation with RL intensity comparable to these commercial scintillators (

Figure 3d). Although the PLQY of

[CuI(dppb)]2 crystal is lower than

[CuBr(dppb)]2 crystal, it has higher RL intensity probably due to its stronger X-ray absorption of I atom. Benefited from the strong X-ray absorption and high exciton utilization,

[CuI(dppb)]2 crystal exhibits a high light yield of up to 19356.7 photons/MeV. The RL spectra of

[CuX(dppb)]2 at different X-ray dose rates were recorded. As shown in

Figure 3e and Figure S14 (see Supporting Information), the RL intensity of

[CuX(dppb)]2 increases monotonically and exhibits a good linear response in the range of 0.688 μGy/s to 278 μGy/s. The limit of detection (LOD) values at a signal-to-noise ratio of 3 were evaluated to be 186 and 158 nGy/s for

[CuBr- (dppb)]2 and

[CuI(dppb)]2, respectively (

Figure 3f), which are significantly lower than the limit for medical X-ray diagnostics (5.5 μGy/s). Moreover, the

[CuI- (dppb)]2 crystals reveal excellent radiation stability with RL intensity keeping nearly unchanged for 130 on-off excitation circles (

Figure 3g). The radiation intensities maintain over 99% even after continuous irradiation at a dose rate of 278 μGy/s for 1800 s.