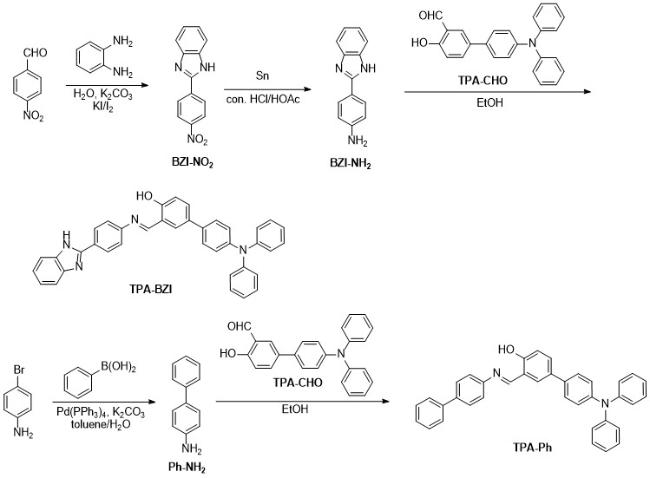

According to the photophysical property tests of six sol- vents mentioned above, it could be easily concluded that CH

3OH was good solvent for the two compounds, but their solubility in water was poor, the fluorescence spectra in CH

3OH/water mixtures in the different volume percentage of water (

fw) were measured. As shown in

Figure 2, for

TPA-BZI, the emission intensity was weak in mixtures of

fw=0% (

Фf=0.261%). Then the emission intensity was minimal when

fw was below 30%, which could be explained that molecules of

TPA-BZI were dispersed in low

fw, and the free rotations of single bonds between molecular functional groups weakened the emission intensities through non-radiative relaxation of the excited state.

[39] Corresponding, the profiles of absorption spectra were almost unchanged, indicating the existence of mono-molecules in mixtures. When

fw was increased to 40%, the emission intensity began to enhance but the profile of absorption spectrum did not evident change, which demonstrated that dispersed mono-molecules began to cluster together, this restricted the intermolecular motions and non-radiative relaxation. And then the emission intensities were continuously "enhanced as

fw exceeded 40%. Moreover, the tails of absorption spectra were significantly upward-shifted and the absorption bands of the ICT were sharply intensified in mixtures of

fw=50% (

Фf=0.595%), which insinuated that the aggregates had been formed,

[40] the luminescence colors were also observed to undergo a significant change. The emission intensity reached to its maximum at

fw=90% (

Фf=1.85%), as the formed aggregates restricted intramolecular rotation, thereby opening the radiative transition pathway. It was the well-known AIE phenomenon. Then emission intensity was again diminished due to rapid molecular aggregation and the shielding of internal molecules in high

fw. For

TPA-Ph, the emission intensity was also weak in mixtures of

fw=0% (Ф

f=0.0256%), thereafter, the emission intensities were slowly strengthened but the profiles of absorption spectra were almost unchanged. When

fw was increased to 60% (

Фf=0.9%), there was a noticeable change in the profile of absorption spectrum, indicating the formation of aggregates. A sharp increase in the emission intensity was observed as shown in

Figure 2(b). It reached a maximum at

fw=70% (

Фf=1.45%), and then the intensities were gradually decreased. By and large, the variation trend of the emission intensities and absorption spectra of

TPA- Ph was similar to that of

TPA-BZI, exhibiting AIE effect.